Introduction

The story of the United States is one of constant contradiction. A land dedicated to the proposition that “all men are created equal” simultaneously held people in bondage. Or, how a nation that purportedly cares for human rights often subverts those values on the world stage.

There’s always been a push and pull between the two poles of American political life: that of the republic and that of the empire. The republic is a society that is dedicated to freedom, equality, the rule of law, and human rights. It’s the society of the Emancipation Proclamation, the New Deal, the Civil Rights movement, and the Great Society. And then there’s the empire, a beast often at war with not only other nations but with the people of its own land. This is the nation that led a genocide against the native population, that forced millions into slavery, that waged wars against smaller nations based upon lies, and dropped the atomic bomb. This tension, this turmoil, is built into the foundation of the United States.

The six books that comprise this collection of reviews tells this story from a variety of vantage points. Kai Bird and Martin J. Shermin’s American Prometheus, the quintessential book on J. Robert Oppenheimer, the father of the atomic bomb, explores a complicated man whose work played a pivotal role in the development of the national security state. President Jimmy Carter’s exegesis on the Israeli/Palestinian conflict outlines the history and complexity of such an epoch-defining struggle, especially as it relates to human rights.

With Nick Turse and Corporal John Musgrave, we get a window into the atrocities committed by the American military during the Vietnam War and the valiant efforts of those who resisted the lies and moral failings of that conflict and the political class who pushed for it. And in the final two books of this collection, we peer into the corporate destruction of the news media and the purposeful obfuscation of the legacy of American populism.

The United States is an empire, despite its democratic pretensions, and it is up to an informed citizenry to counteract that nefarious trajectory and reassert the values of the republic. The books discussed below provide us with the tools to do just that.

American Prometheus: The Triumph and Tragedy of J. Robert Oppenheimer by Kai Bird and Martin J. Sherwin (2005)

The story of J. Robert Oppenheimer, the father of the Atomic Bomb, is again a figure of intense interest, mostly due to Christopher Nolan’s Academy-Award winning film on the famous physicist. But what inspired Nolan to make a film about the changing dynamics of science, politics, and policy at the height of the “American Century”?

It was biographers Kai Bird and Martin J. Sherwin’s magisterial book, American Prometheus: The Triumph and Tragedy of J. Robert Oppenheimer (2005). The effort of over 25 years of research, this book is the definitive account of the life of one of the most consequential figures of the twentieth century, and in some respects, all of human history.

Born to Jewish immigrant parents and raised in the Ethical Culture School in New York, J. Robert Oppenheimer was an intense and gifted student whose passions varied from poetry to physics. It was ultimately the latter that would become his life’s work. After a tumultuous period in England, he finally went to Göttingen, where he studied under, and collaborated with, famed physicist Max Born. He then came back to the US, establishing the theoretical physics department at UC Berkeley, as well as engaging in left-wing political activities which would haunt him for decades.

Of course, “Oppie” is best remembered for running the Manhattan Project at Los Alamos, New Mexico, whose team he directed successfully built and tested the first atomic bomb in July of 1945. A month later, the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki were another earth-shattering event that haunted him as well.

Oppenheimer was the most high-profile casualty of McCarthyism, when his security clearance was revoked in 1954 due to his connections to the Communist Party, which he maintained he was never a member of. He died in 1967 from esophageal cancer, the result of years of tobacco use.

Bird and Sherwin’s narrative is crisp, deeply researched, and meticulously detailed. It provides readers not only a striking portrait of Oppenheimer but a political history of the origins of the Cold War and the Military-Industrial Complex. It is an essential read about an essential figure in world history.

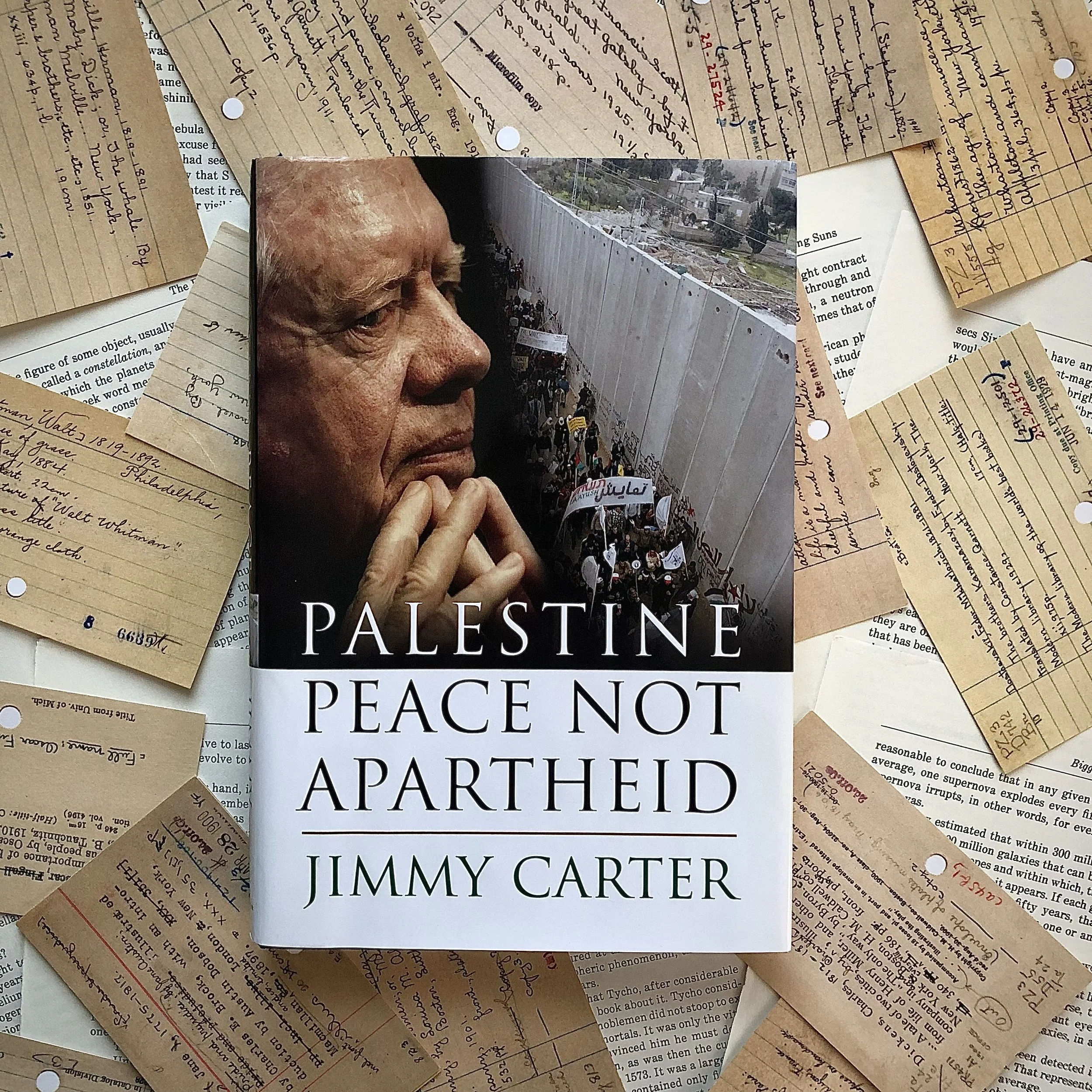

Palestine: Peace Not Apartheid by Jimmy Carter (2006)

For months, the ongoing genocide in Gaza by the government of Israel, in response to terrorist attacks by Hamas on October 7, 2023, have been in the forefront of people’s minds. How did things get to this terrible place?

One person who can shine a light on this question is President Jimmy Carter, who has spent a lifetime studying the middle east and the conflicts that have ravaged its borders for decades. In 1978, he helped Egypt and Israel negotiate a peace treaty that ended hostilities between the two nations and started the framework for a lasting peace with justice in the region. Since leaving the White House, he and his organization, the Carter Center, have overseen elections in Gaza and participated in continuing efforts to create real change for the people of Israel and Palestine.

In Palestine: Peace Not Apartheid (2006), Carter provides a wide-ranging survey of the history, politics, and key players in the conflict, and what his role in the continuing discussion has been. As a man of faith dedicated to the cause of human rights, Carter acknowledges that there are real divides between the Israeli and Palestinian people that have led to the deteriorating conditions we see today. He has also not shied away from criticism of Israel, particularly in its violation of UN Resolutions 242 and 338, which explicitly ban settlements in the territories of Gaza and the West Bank. Additionally, he’s met with Palestinian leaders and everyday citizens to witness the truly barbaric bifurcation of their society from the state of Israel, from military courts handling all disputes to the construction of heavily guarded walls,

He argues that the most realistic and humane option is for a two-state solution, with full political, social and economic rights for Israelis and Palestinians, predicated on the removal of settlements and a commitment to democratic elections in both states.

While his narrative is dated somewhat, it nevertheless gives readers the context one needs, especially with a timeline of events and an appendix of documents. Palestine: Peace Not Apartheid is one of Carter’s best books and a must-read for those interested in learning about the conflict.

Dollarocracy by John Nichols and Robert McChesney (2013)

Dollarocracy by John Nichols and Robert McChesney (2013) is a thoroughgoing analysis of the interrelationship between money, media, and modern politics. Written in the aftermath of the 2012 elections, which at that time were the most expensive in American history, this book blows the lid off of all the ways money and media corrupt American democracy. The chapter devoted to the aforementioned elections is particularly enlightening. Added all together, the 2012 elections, from the presidential race all the way down to local races, cost $10 billion, mostly from wealthy individuals and corporations. It was also the first election after the disastrous Citizens United decision from the Supreme Court, which allowed for unmitigated flows of dark money into elections, as the court affirmed definitively that money was a form of speech. Not a promising sign of democracy meaning “one person, one vote.”

So, how does the media play into all this? Local TV stations, whose owners are mostly media conglomerates disconnected from the communities they serve, amass most of their revenue through political advertising. As a result, the majority of information that viewers receive is through advertising rather than political reporting. This leaves most citizens left to figure out anything about the candidates vying for their vote, since public broadcasting isn’t large enough to be a countervailing force and local journalism is at an all-time low.

To remedy this crisis, they call for constitutional reforms that limit political advertising, curtail corporate influence in elections, and codify voting rights for all citizens— which the United States still doesn’t have. These reforms would go a long way to rehabilitate democracy in America, but they also require large social movements to get them done.

I really liked this book and it’s a great companion book to classic works on the media like Chomsky and Herman’s Manufacturing Consent and Michael Parenti’s Inventing Reality. While their examples are dated, their arguments are more relevant than ever. We need a society of engaged citizens, not consumers choosing candidates like they would toothpaste. That would be a real democratic society.

Kill Anything That Moves: The Real American War in Vietnam by Nick Turse (2013)

For many, the television coverage of the War in Vietnam was the first time they had seen the horrors of war up close. This was especially evident with the “My Lai Massacre” on March 16, 1968, where American soldiers slaughtered over 300 innocent civilians. Only one man, Lieutenant William Calley, was held legally responsible for the massacre, and even his lengthy prison sentence was commuted by President Richard Nixon.

Historians and media figures often tell the public that the My Lai Massacre was an aberration, that very few in the American military killed innocent people in Vietnam. Investigative journalist Nick Turse has dispelled that notion once and for all with his landmark book, Kill Anything That Moves: The Real American War in Vietnam (2013). Pouring through first-hand testimonies and declassified documents, Turse shows how American soldiers perpetrated war crimes throughout the United States’ imperialist military action in Vietnam.

From young women in Quang Tin province trying to salvage their homes and the remains of their loved ones to the burning of civilians in the Mekong Delta, Americans routinely killed Vietnamese civilians and then claimed them as enemy “VC,” or “Viet Cong.” Since the Vietnam war’s progress was measured by US planners in terms of body count rather than the traditional metric of territory captured, the incentive to kill as many people as possible was ever present, regardless of their status.

Alongside murder, there was rampant sexual violence, torture, and mutilation of human beings, many of whom were innocent civilians. While the majority of US combat troops didn’t commit these heinous acts, a sizable minority did and the US government did everything they could to cover up these crimes and protect those responsible.

Turse is a resolute journalist who tracked down American veterans who knew or were involved in war crimes as well as Vietnamese civilians who fortunately lived to tell their stories. His book is not an easy read, but a vital one, for the dehumanization we see all around the world, from Palestinians and Sudanese to so many others, finds a tragic antecedent in the War in Vietnam.

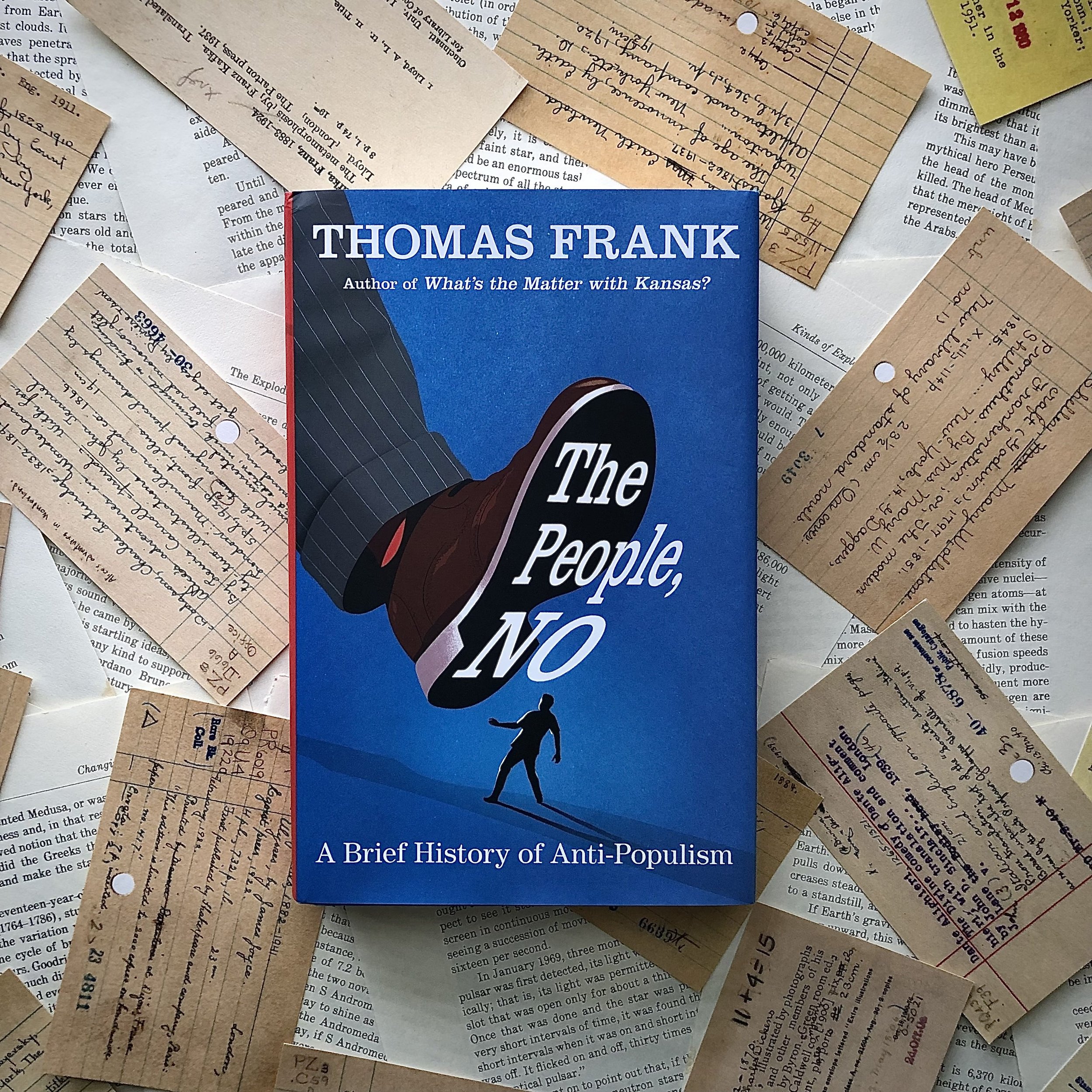

The People, No: A Brief History of Anti-Populism by Thomas Frank (2020)

Populism as a political phenomenon is mostly known today for its wickedness— comprising a rabble of racists and reactionaries whose sole goal is to regress a society to a supposed “better age.” But the ideal of populism didn’t start this way. As journalist and historian Thomas Frank recounts in his marvelous book, The People, No: A Brief History of Anti-Populism (2020), the term populist was explicitly invented in the 1890s as a means to describe a left-wing politics that stood up to big business and its protectors in government. From the trailblazing candidacy of William Jennings Bryan in 1896 all the way through the New Deal era of Franklin Delano Roosevelt, populism was a movement dedicated to removing artificial barriers of privilege and power towards building real democracy.

But as the term was explicitly invented, the reaction towards it was equally invented. From the priests of academe, notably scholars such as Richard Hofstader, the term lost its original meaning and was warped, without evidence, into the right-wing demagoguery we envision today. Frank reviews the historical record to show how these scholars of “populist studies” created a chimera divorced from the social-justice oriented movement stretching from the 1890s through the 1930s, and in so doing, undermining the genuinely democratic aspirations of that movement. Additionally, he adeptly traces how the anti-populism of the 1890s-1930s, mostly right-wing and menacingly pro-business, evolved into the anti-populism of the technocratic, neoliberal elites today, primarily ensconced in the Democratic party. This sad state of affairs is how we get to figures like Donald Trump, a billionaire who spent most of his life sneering at the rabble, rebranded as a man of the people to the detriment of working-class politics.

Frank is a delight to read; I’ve read many of his books and find him an excellent scholar and a masterful writer. His passion for the history of working people in America is so inspiring, and his frustration with the ruling class’s interpretation of populism is completely justified. The People, No is a perfect antidote to the court historians who have distorted America’s proletarian past.

The Education of Corporal John Musgrave: Vietnam and Its Aftermath by John Musgrave (2021)

As a person who grew up during the invasion of Iraq, I learned about the Vietnam War in comparison to that needless war. Vietnam represented for a generation or two before me the same lies, failures, and futilities of war as Iraq did for me. No one experienced this more than soldiers themselves. Many young Americans had their lives shattered by their time in Vietnam— losing a limb, enduring PTSD, and facing disrespect once they got home— not to mention the millions of Vietnamese lives that were destroyed in that conflict.

One veteran who knows this experience well is Corporal John Musgrave of the U.S. Marine Corps, who spent nearly a year in combat in Vietnam. He shares his story in one of the most poignant memoirs I have ever read, The Education of Corporal John Musgrave: Vietnam and Its Aftermath (2021). A contributor to Lynn Novick and Ken Burns’s magisterial documentary series, the Vietnam War, Musgrave has led a life of service, sacrifice, and perseverance which comes through on every page in this book.

Growing up in Independence, Missouri, Musgrave never wanted to be anything more than an U.S. Marine, hearing of his father’s service in WWII. At the age of 17, he enlisted in the Marines and was shipped off for basic training, combat training, and finally, to Vietnam, where he served for 11 months in Danang and Con Thien, among other areas. His harrowing reflections on the conditions of war— poorly made weaponry, jungle rot, and fighting the enemy— culminated in his injury in battle in 1968, where he nearly died.

Adjusting to civilian life was hard for Musgrave, who turned to alcohol to numb the pain, but he endured, ultimately becoming one of the most public faces of Vietnam Veterans Against the War. As he learned about the war he recognized it for what it was: a futile conflict cooked up by Washington to save face against the supposed scourge of Communism, which ultimately tore the US apart and forever maimed a generation of Americans and Vietnamese.

Musgrave’s story is so powerful because of his vulnerability, his humility, and his desire to make sense of something so senseless. It is an indispensable contribution to the literature on Vietnam.